Body Image and Your Sexual Health

If you’re struggling with body image concerns, it makes sense that you may also have struggles with sex. Sexual intimacy brings many of the ultimate forms of vulnerability together, and if you don’t feel comfortable with your body, you might find it difficult to connect and enjoy sexual experiences with a partner.

Here are a couple of things I hope you’ll remember if body image struggles are impacting your sexual relationship.

Here are a couple of things I hope you’ll remember if body image struggles are impacting your sexual relationship.

First, you don’t have to have a “perfect” body in order to enjoy sex. Despite what the media has portrayed for the last several decades, people in a variety of bodies can have fulfilling, meaningful, enjoyable sexual relationships. While the media might insist that you must be young, thin, conventionally attractive, and able-bodied to have and enjoy sexual experiences, this is simply not true. In real life, people in bodies of varying sizes, abilities, and ages are enjoying meaningful sexual connection. It’s true! People with acne, stretch marks, cellulite, wrinkles, body hair, and hair loss can and do enjoy loving, healthy sexual connection. The same goes for people in bodies with chronic illness, limb differences, ostomy bags, movement disorders, visual impairment, or other conditions.

Second, while body image happens in the mind (our thoughts, perceptions, and beliefs about our bodies), satisfying sex happens mostly in the body. The biggest thing you can do to help yourself when body image struggles interfere with sexual connection is this: reconnect with the experience of being in your body. When your mind starts pulling your attention toward body criticism or self-conscious thoughts, remember that your bodily sensations are your anchor for sexual connection. If you intentionally connect with your senses and let your mind be present, you can help yourself through negative body image thoughts.

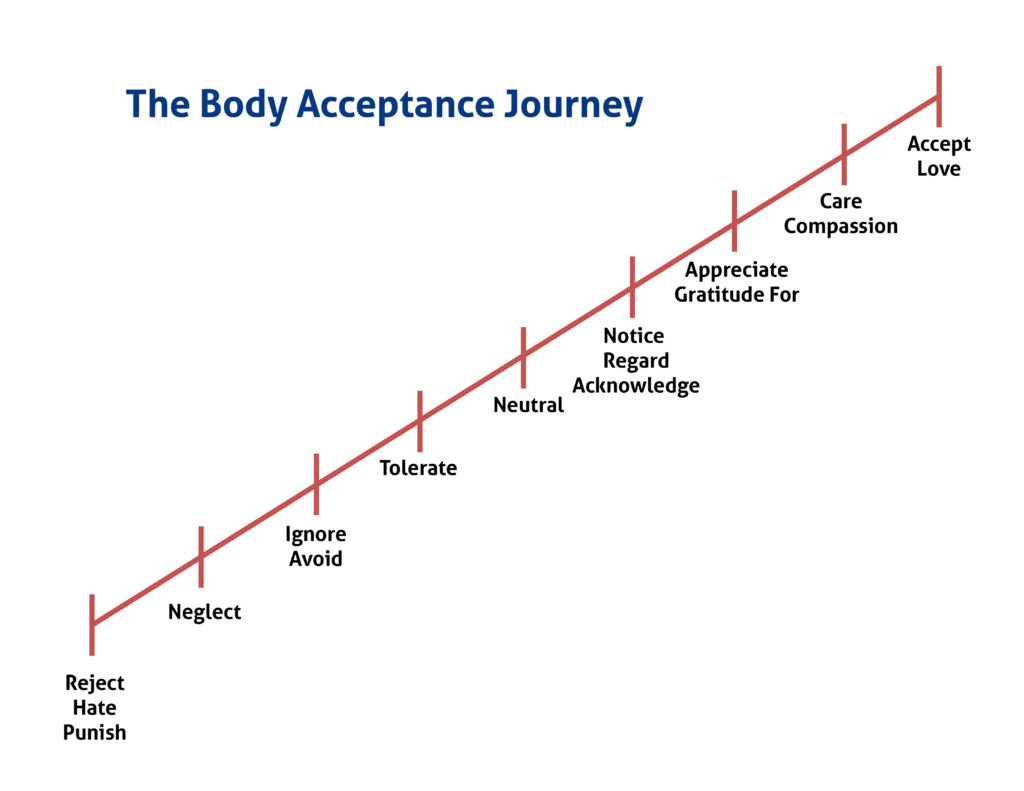

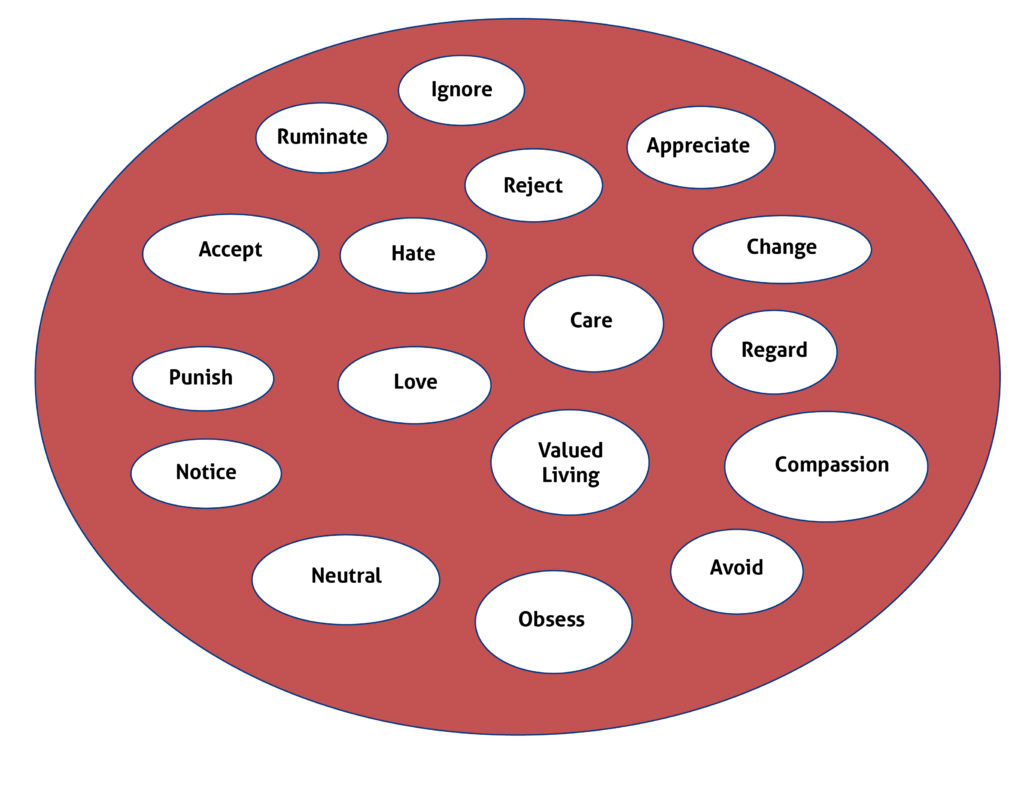

All of this is easier said than done, of course. Working through body image struggles can be a complex journey. Seeking support from therapy, learning about sexual and relationship health, and having honest conversations with your partner are all excellent ways to help yourself work through body image struggles.

This topic is important to me as a marriage and family therapist. I really believe that healthy relationships are the backbone of our wellbeing as a human race, and I care about helping people find ways to strengthen positive connections with themselves and their partners. All people deserve to feel comfortable and confident in their bodies and in their relationships. Here are some other resources to support you in the realm of body image and relationships:

More Than a Body by Dr. Lindsay Kite and Dr. Lexie Kite

Come as You Are by Emily Nagoski, PhD

Other blog posts: Navigating Recovery While In a Relationship, Part 1 and Part 2

And coming soon, Balance Health and Healing will be launching an online course I created called Body Image and Sex! The course is meant to help you overcome body image struggles and improve your sexual relationship.

I’m excited to share it with you! Join the Waitlist here.

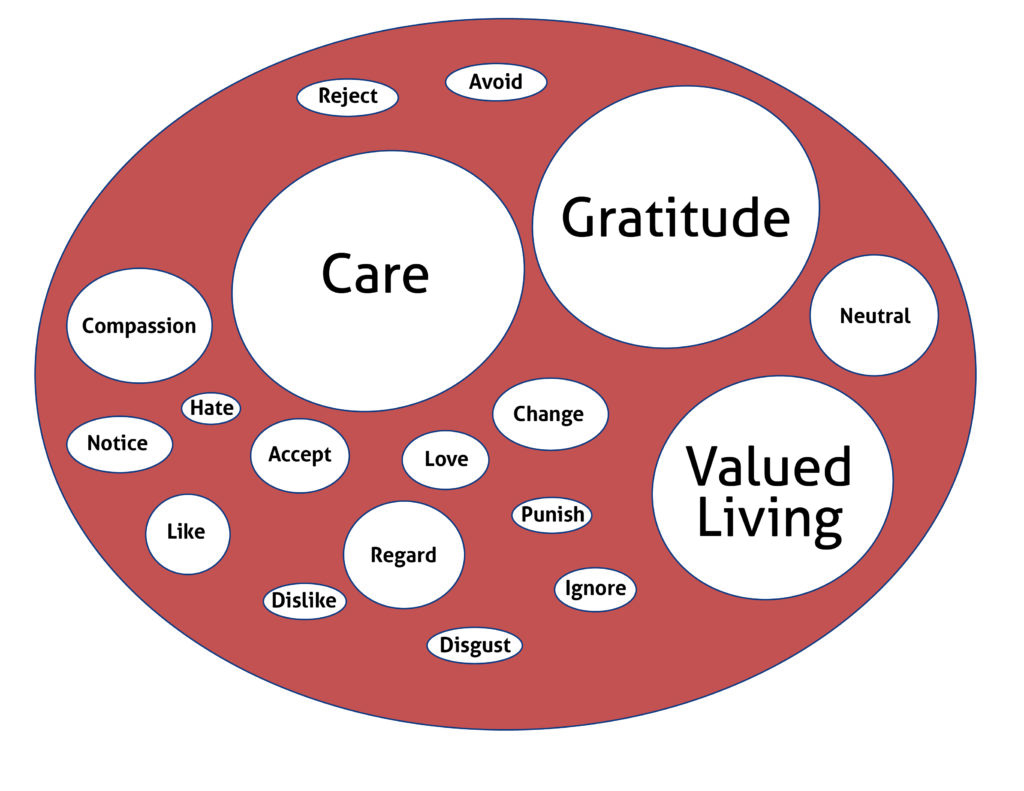

“Let It Go Day” is a great reminder that hanging on to grudges, regrets, and past hurts can really drag us down. These negative feelings can cause stress, anxiety, and depression. Letting go doesn’t mean forgetting or ignoring what happened; it’s about acceptance and acknowledgment while releasing its hold on our present and future.

“Let It Go Day” is a great reminder that hanging on to grudges, regrets, and past hurts can really drag us down. These negative feelings can cause stress, anxiety, and depression. Letting go doesn’t mean forgetting or ignoring what happened; it’s about acceptance and acknowledgment while releasing its hold on our present and future.

Throughout our lives, we as humans experience a variety of emotions. Whether they are comfortable emotions such as feeling powerful, inspired, happy, or heavier emotions such as feeling insecure, overwhelmed, or disappointed, food can be a powerful way to find connection throughout it all.

Throughout our lives, we as humans experience a variety of emotions. Whether they are comfortable emotions such as feeling powerful, inspired, happy, or heavier emotions such as feeling insecure, overwhelmed, or disappointed, food can be a powerful way to find connection throughout it all.

1: Eat enough, often enough

1: Eat enough, often enough

A letter to my postpartum body:

A letter to my postpartum body:

My relationship with movement has shifted significantly over the past five years. Growing up playing competitive soccer influenced the way I viewed movement and its purpose in my life. In my younger years, I was not thinking about what my body looked like as I ran, tackled, passed, and shot. Competing in matches and practicing with my best friends was invigorating. On the field, I felt truly embodied, defined by Dr. Hillary McBride in her book

My relationship with movement has shifted significantly over the past five years. Growing up playing competitive soccer influenced the way I viewed movement and its purpose in my life. In my younger years, I was not thinking about what my body looked like as I ran, tackled, passed, and shot. Competing in matches and practicing with my best friends was invigorating. On the field, I felt truly embodied, defined by Dr. Hillary McBride in her book