A New Way to Think About Body Acceptance

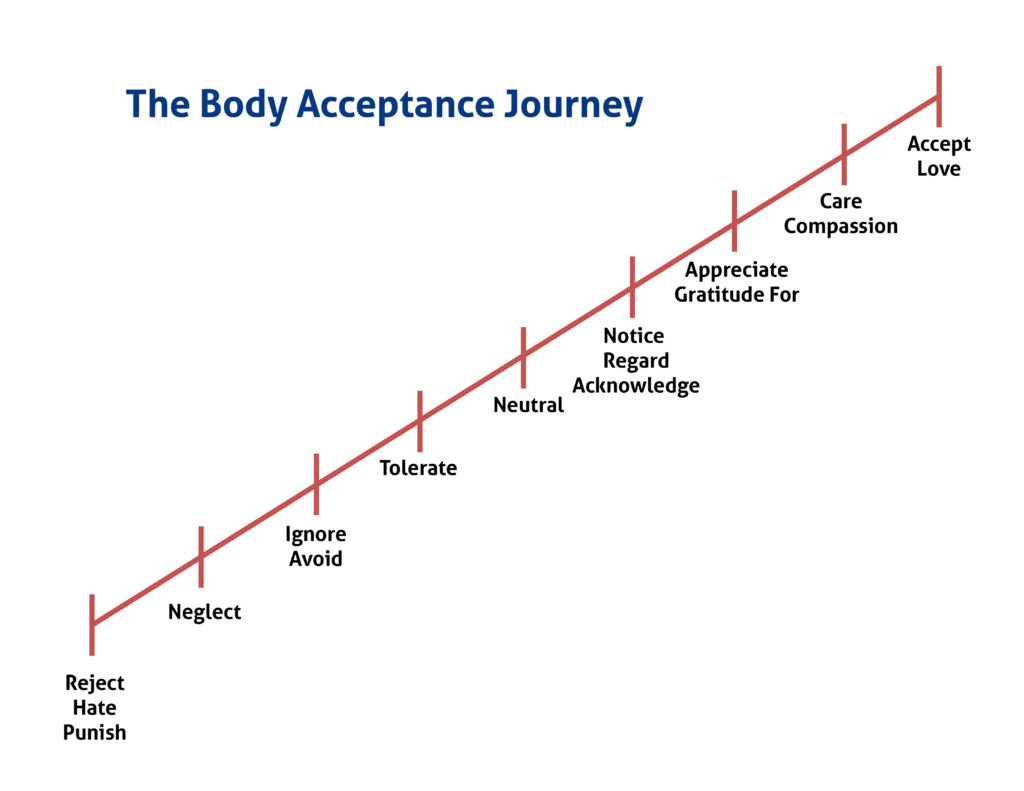

I am passionate about body acceptance work. I teach it, practice it, and continue to learn and evolve my understanding of how to do this work. The body acceptance journey is often described using the metaphor of a ladder. In fact, when I lecture about body acceptance, I use the following image to capture the idea:

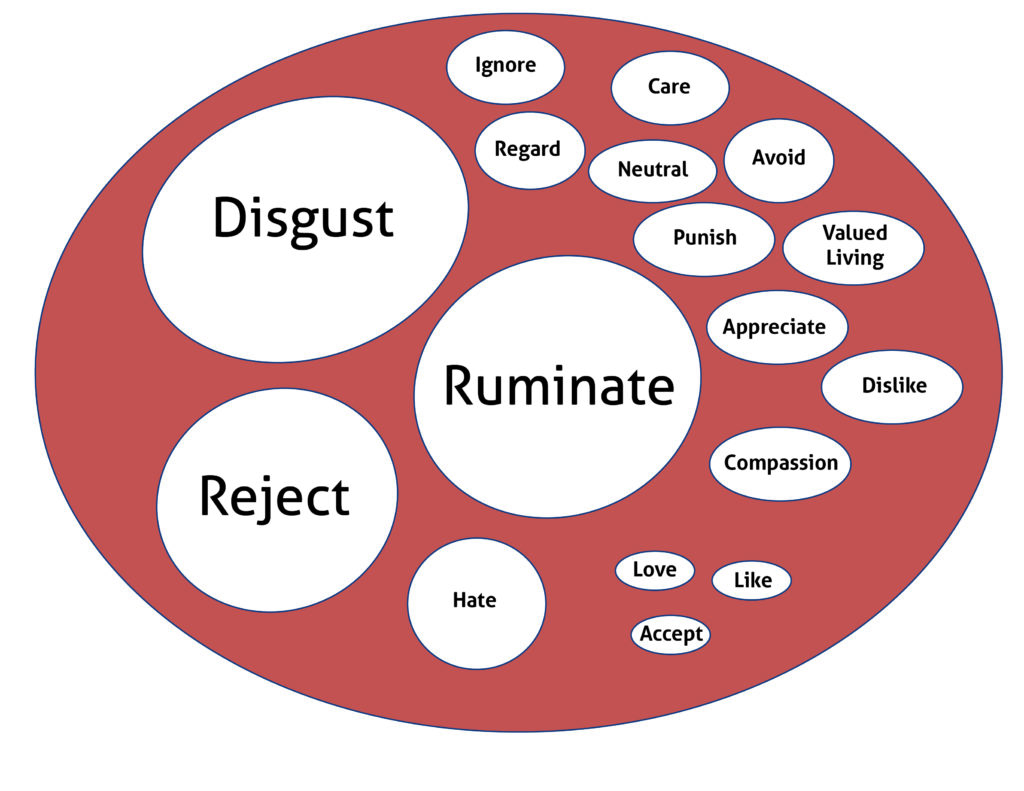

However, when we used this image in our Body Acceptance Group this last month, my understanding of this “progressive approach” was turned on its head. So many clients share about how they can be in a more accepting or healthy place with their body one day and, the next, feel right back at “ground zero.” Others describe how they can inhabit multiple places with their body at once. For example, they can feel grateful for their body while also feeling disgust for how it looks. They can feel compassion for what their body has gone through and also resent that it refuses to change the way they want it to change. It suddenly became clear in this discussion that the ladder doesn’t fit these experiences at all. I know body acceptance is a non-linear journey, but when we talk about progress, we talk about being in different places than we were before. It’s as if we keep arriving or stepping up to somewhere new, and different, and stable. The journey is so much more fluid and complicated than that. In this group, I suddenly envisioned a better way to conceptualize the body acceptance journey. And it’s one of bubbles.

However, when we used this image in our Body Acceptance Group this last month, my understanding of this “progressive approach” was turned on its head. So many clients share about how they can be in a more accepting or healthy place with their body one day and, the next, feel right back at “ground zero.” Others describe how they can inhabit multiple places with their body at once. For example, they can feel grateful for their body while also feeling disgust for how it looks. They can feel compassion for what their body has gone through and also resent that it refuses to change the way they want it to change. It suddenly became clear in this discussion that the ladder doesn’t fit these experiences at all. I know body acceptance is a non-linear journey, but when we talk about progress, we talk about being in different places than we were before. It’s as if we keep arriving or stepping up to somewhere new, and different, and stable. The journey is so much more fluid and complicated than that. In this group, I suddenly envisioned a better way to conceptualize the body acceptance journey. And it’s one of bubbles.

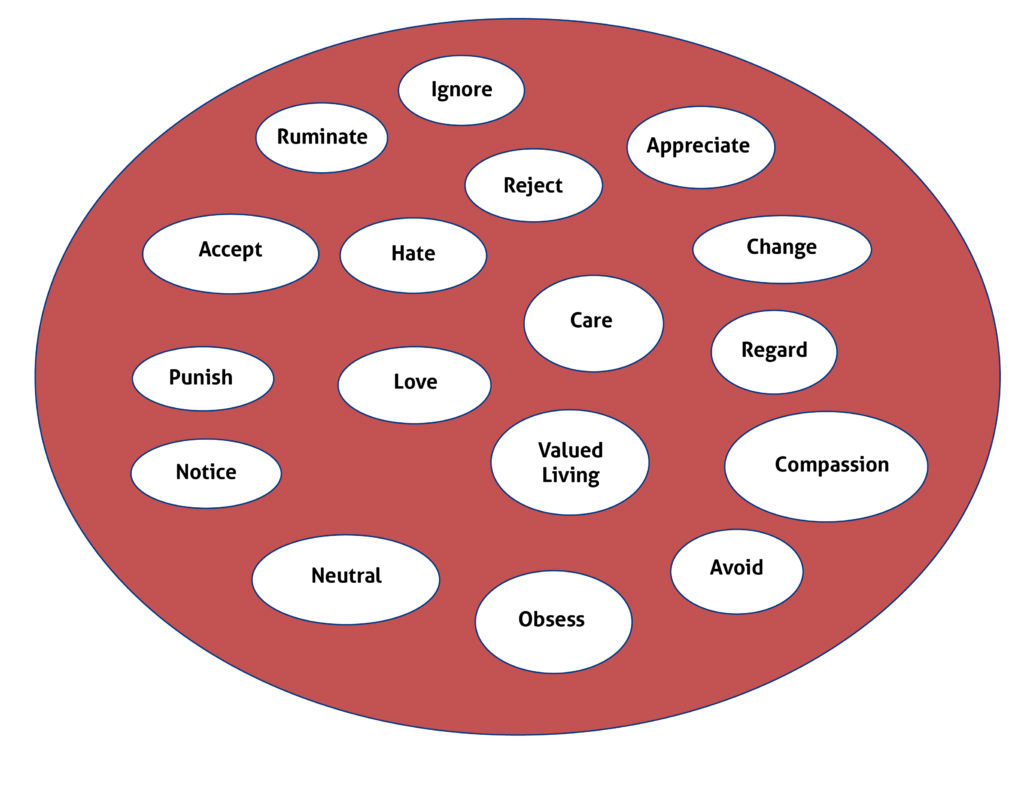

Our experiences and relationships with our bodies are deeply rich, historical, personal, complicated, and nuanced. In a holistic perspective, we always carry with us each of these lived feelings, perceptions, beliefs, and behaviors in our bodies. Sometimes certain bubbles expand and take up a lot of room. For example, an event or interaction in our lives may trigger more negative feelings about our bodies. Or maybe we are feeling more vulnerable in general and are more prone to feel amplified negative emotions about our bodies.

Our experiences and relationships with our bodies are deeply rich, historical, personal, complicated, and nuanced. In a holistic perspective, we always carry with us each of these lived feelings, perceptions, beliefs, and behaviors in our bodies. Sometimes certain bubbles expand and take up a lot of room. For example, an event or interaction in our lives may trigger more negative feelings about our bodies. Or maybe we are feeling more vulnerable in general and are more prone to feel amplified negative emotions about our bodies.

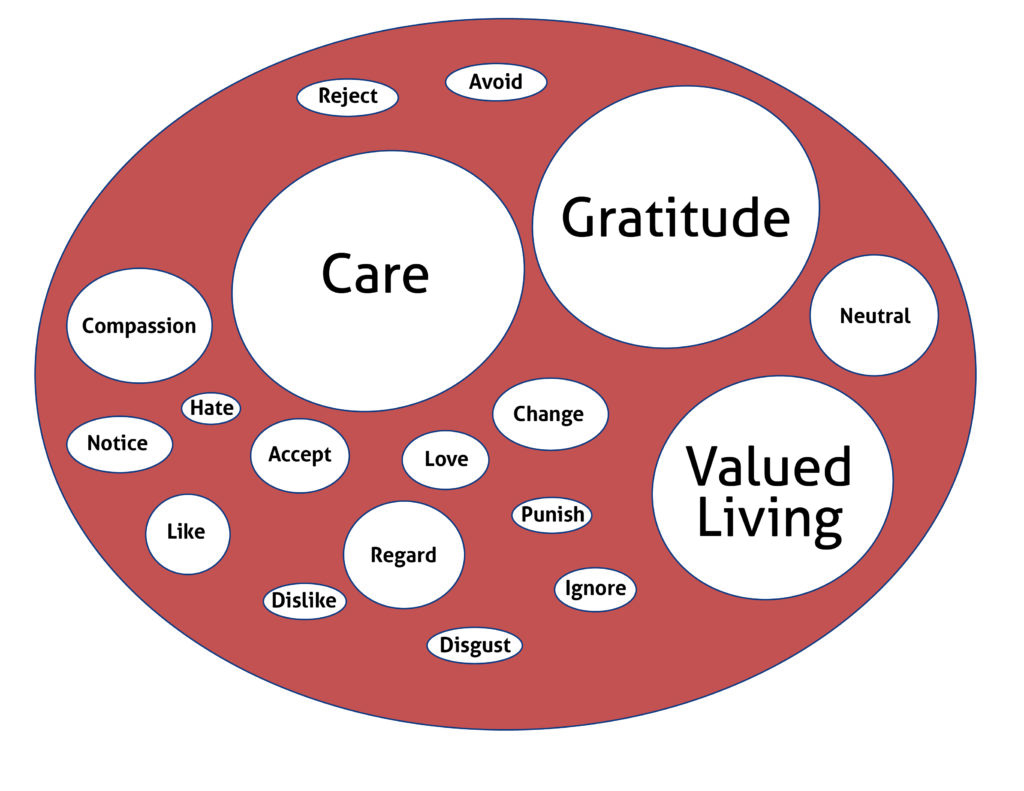

Through body acceptance work, there is active movement to amplify and grow different ways of being with our bodies. There is choice in what works for you and what you value, and this journey involves a lot of trial and error and hard work. For some people they really resonate with amplifying body gratitude and find a lot of joy and relief in this. For others, maybe they want to focus even less on their bodies and so focus on identifying and living more intentionally, their values (valued living) and feel a lot of relief in doing so. Some enjoy experimenting, growing skills, and amplifying many different ways of being with their bodies and find at different times, different tools and orientation work better than others. In this work, you will notice these other experiences you are intentionally amplifying will take up more space in your lived reality with your body. And while this doesn’t make more painful experiences or beliefs disappear completely, it changes the overall experience with yourself.

Through body acceptance work, there is active movement to amplify and grow different ways of being with our bodies. There is choice in what works for you and what you value, and this journey involves a lot of trial and error and hard work. For some people they really resonate with amplifying body gratitude and find a lot of joy and relief in this. For others, maybe they want to focus even less on their bodies and so focus on identifying and living more intentionally, their values (valued living) and feel a lot of relief in doing so. Some enjoy experimenting, growing skills, and amplifying many different ways of being with their bodies and find at different times, different tools and orientation work better than others. In this work, you will notice these other experiences you are intentionally amplifying will take up more space in your lived reality with your body. And while this doesn’t make more painful experiences or beliefs disappear completely, it changes the overall experience with yourself.

This lived experience in your body is a moving, changing, fluid experience. As we work, we build confidence and more stability in inviting and amplifying the experiences, feelings, and beliefs we want to have in our bodies. But this doesn’t mean hard days disappear where other feelings and experiences rear their heads and dominate the day.

This lived experience in your body is a moving, changing, fluid experience. As we work, we build confidence and more stability in inviting and amplifying the experiences, feelings, and beliefs we want to have in our bodies. But this doesn’t mean hard days disappear where other feelings and experiences rear their heads and dominate the day.

There is no “falling backwards” or “getting worse” with this framework of body acceptance. It is simply awareness that certain bubbles are larger today, or this week, and this affects how we feel. We can make conscious choices to use the tools and knowledge we have to attend to the bubbles we want to grow and amplify and have compassion for ourselves on days we are simply doing our best to get by. The body acceptance journey, just like mediation, is a practice, not a final destination. Over time it is easier and more and more rewarding, and it continues to invite us to work and be with ourselves in intentional ways as we move through this messy experience that is life.

1: Eat enough, often enough

1: Eat enough, often enough

Ketamine, originally developed as an anesthetic, has garnered attention in recent years for its potential in treating various mental health conditions, including depression, anxiety, and PTSD, and its role in stress management is equally noteworthy.

Ketamine, originally developed as an anesthetic, has garnered attention in recent years for its potential in treating various mental health conditions, including depression, anxiety, and PTSD, and its role in stress management is equally noteworthy.

A letter to my postpartum body:

A letter to my postpartum body:

My relationship with movement has shifted significantly over the past five years. Growing up playing competitive soccer influenced the way I viewed movement and its purpose in my life. In my younger years, I was not thinking about what my body looked like as I ran, tackled, passed, and shot. Competing in matches and practicing with my best friends was invigorating. On the field, I felt truly embodied, defined by Dr. Hillary McBride in her book

My relationship with movement has shifted significantly over the past five years. Growing up playing competitive soccer influenced the way I viewed movement and its purpose in my life. In my younger years, I was not thinking about what my body looked like as I ran, tackled, passed, and shot. Competing in matches and practicing with my best friends was invigorating. On the field, I felt truly embodied, defined by Dr. Hillary McBride in her book